Identity over resolutions: The quiet work of Becoming

6 mins read

By Dr Chantale Lussier, PhD. CMCP

The turning of the calendar is a natural invitation to pause. Everywhere we look, there are slogans promising seemingly overnight reinvention and transformation: “new year, new me,” ambitious new year’s resolutions, or lists of self-improvement targets. And yet, transformation is rarely found in slogans. True change is quieter, subtler, and far more intimate.

The work of transformation begins not with the calendar but with identity and beliefs. It begins with noticing the stories we tell ourselves about who we are, what we are capable of, and what we deserve. These narratives, often unconscious, shape our choices, focus, behaviours, and performance more than any external goal ever could (Markus & Wurf, 1987; Bandura, 1997).

Whether you are an athlete stepping into a pivotal season, a professional navigating a career shift, or anyone approaching a life transition, understanding and shifting your identity and its related internal narratives is the foundation of meaningful change.

Do you know the key stories you keep telling yourself about yourself? Are these helpful and empowering or creating resistance, self sabotage, and self limiting beliefs and habitual patterns in your life?

Why This Matters Now

The new year is culturally framed as a pivot point. This social context makes reflection natural, but reflection without insight, strategies, and wisdom can slip into self-criticism. Many people feel the pressure to “be better” without first asking: better according to whom, and based on what internal assumptions?

The work that matters at this time of year is to examine the beliefs that shape your actions. Limiting beliefs are assumptions we carry that quietly constrain our potential:

• “I’m not disciplined enough.”

• “I’ll never perform under pressure.”

• “I’m not the kind of person who can do this.”

These beliefs are learned patterns, often formed from early experiences, social comparisons, or repeated and now highly rehearsed self-talk. The good news is that these patterns are not fixed. Neuroscience confirms that the brain is remarkably plastic; neural pathways can be strengthened, weakened, or rewired through intentional reflection and practice (Davidson & McEwen, 2012). Likewise, sports psychology shows that self-efficacy and identity are dynamic and can be developed over time (Bandura, 1997; Vealey, 2007).

“If you accept a limiting belief, it will become a truth for you” Louise Hay

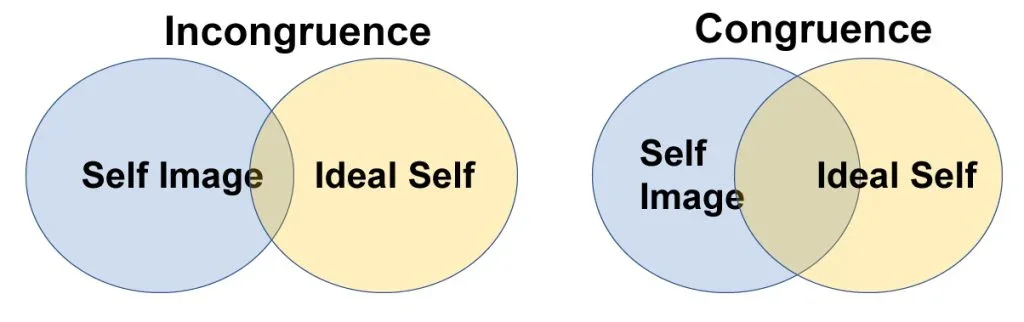

Our self-concept is not always aligned with reality. As Carl Rogers explained, when it is aligned, it is said to be congruent. If there is a mismatch between how you see yourself (your self-image) and who you wish you were (your ideal self), your self-concept is incongruent. This incongruence can negatively affect self-esteem (Cherry, K. 2025).

In my practice over the last 20 years, I have seen that a vast majority of people hold highly inaccurate, poor self image which deeply impacts the beliefs they hold and the stories they tell themselves. Part of effective mental skills training can involve enhancing the accuracy and quality of one’s self concept and designing personally meaningful self talk that is in better alignment with their current and aspirational self.

The Science of Identity and Beliefs

Identity, the sense of who we are, guides how we interpret experiences and informs our behavior. Markus and Wurf (1987) describe identity as dynamic, constantly shaped by context, feedback, and internalized beliefs. If someone has internalized the belief, “I’m not a leader,” they are likely to unconsciously avoid opportunities to act in leadership roles, even when the skills are present.

Limiting beliefs operate similarly: they create self-imposed constraints. Beilock and Carr (2001) show that under pressure, overthinking can disrupt automatic, well-learned skills. In other words, what we believe about ourselves can directly affect our performance, even when skill and preparation are present.

However, identity and beliefs are not static. With intentional practice, awareness, and behavioral experiments, we can challenge limiting beliefs, reinforce adaptive narratives, and expand our capacity to perform under pressure or embrace new opportunities.

Can you think of a few beliefs you have held onto that have likely been limiting how you show up in the world, be it with your family, in friendships and relationships, and/or in your school, work, and/or performance contexts?

Practical Strategies for Transforming Limiting Beliefs

1. Notice the stories you tell yourself

The first step is awareness. Pay attention to recurring self-talk, assumptions, and judgments about yourself. Journaling is a simple and effective tool: write down thoughts that come up when you face challenges, opportunities, or pressure.

Exercise: For one week, jot down moments when you hesitate, self-criticize, or doubt yourself. Look for recurring themes; these are often your limiting beliefs in disguise.

2. Question the narrative

Ask: Is this belief universally true? Is it serving me? Where did it come from? Limiting beliefs are often historical; they may have been adaptive in a past context but no longer serve your present or future.

Tip: Reframe your internal dialogue. For example, replace “I always fail under pressure” with “Pressure signals opportunity to practice focus; I have skills to manage it.”

3. Experiment with small actions

Beliefs are embedded in behavior. To change them, take micro-actions that contradict the limiting belief. If you believe you “crumble under pressure,” practice performing in a slightly challenging, low-risk context, then reflect on the outcome (Beilock & Carr, 2001). Over time, repeated small successes reshape neural pathways and reinforce self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997).

Exercise: Identify a small but meaningful action that challenges your belief. Document the results and notice the evidence contradicting your old story.

4. Anchor in evidence

Keep a “success log” to record moments when you acted against limiting beliefs or performed in ways that felt contrary to your assumptions. Reviewing this evidence reinforces your developing identity and counters the brain’s negativity bias (Davidson & McEwen, 2012).

Tip: Reviewing past best performances and your success log can become a vital part of your performance preparation, be it before your next game or competition, keynote presentation, job interview, or even before your next key social engagement like a date.

5. Practice self-compassion

Identity work can feel uncomfortable. Change is rarely linear. Neuroscience shows that self-compassion reduces stress, supports resilience, and enhances learning under pressure (Neff, 2011).

Tip: Use compassionate language with yourself: “This is hard, and that’s okay. I am learning.” Even brief self-compassion practices can regulate the nervous system and improve performance under challenge.

Why This Matters for Athletes, High Performers, and Anyone in Transition

Athletes: Identity and beliefs influence how you respond to pressure, setbacks, and high-stakes performance. Mental performance training teaches you to perform consistently, even when confidence fluctuates (Vealey, 2007).

High performers / career transitions: Beliefs shape how you approach risk, opportunity, and leadership. Shifting limiting narratives unlocks growth and adaptability.

Life transitions: Whether it’s moving cities, starting a new role, or pursuing next-level opportunities, your beliefs shape your perception of what is possible. Transformation begins here.

Practical Year-End Rituals

1. Reflect, don’t resolve: Instead of making a “new me” list, write about who you want to be, not just what you want to do.

2. Identify one belief to challenge: Choose a belief that most limits you and design a small experiment to test it.

3. Micro-habits over sweeping resolutions: Focus on consistent, small actions that reinforce your evolving identity.

4. Daily awareness practice: One minute per day noticing self-talk and assumptions builds insight and regulation.

Final Thoughts

The calendar turning is a reminder, not a mandate. Transformation doesn’t require erasing who you are or imposing a “new you.” It begins with understanding yourself at a deeper level, identifying the stories that shape your choices, and practicing actions that expand your potential.

This is the work of life coaching, mental performance, and the practice of applied sport psychology: identity-informed, evidence-based, and quietly transformative.

Are you experiencing a significant transition?

Are you feeling in transition after a significant year, season, or big event?

Are you experiencing or planning ahead to a new year, new season, including life and/or career transition of some kind?

Would like support, guidance, and coaching to navigate this meaningful time, then I invite you to take one small, meaningful step today.

Book a free 15-minute discovery call with me here. Let’s explore how to craft the best plan to sustain your excellence as you transition into your next great season and/or chapter in your life.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Beilock, S. L., & Carr, T. H. (2001). On the fragility of skilled performance: What governs choking under pressure? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(4), 701–725. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.4.701

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cherry, K. (2025). What is self concept? Very well mind.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3093

Markus, H., & Wurf, E. (1987). The dynamic self-concept: A social psychological perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 38(1), 299–337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.38.020187.001503

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion: The proven power of being kind to yourself. William Morrow.

Vealey, R. S. (2007). Mental skills training in sport. In G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 287–309). Wiley.